Crop-damaging temperatures increase suicide rates in India

Published August 15, 2017

Read

Last week, the Climate Impact Lab’s Tamma Carleton published a paper in PNAS addressing a topic that has captured the attention of media and policymakers around the world – the rising suicide rate in India. The paper focuses on the role of climate in this tragic phenomenon, finding that temperatures during India’s main growing season cause substantial increases in the suicide rate, amounting to around 65 deaths across the country for each 1°C increase in a single day’s temperature. Carleton’s research shows that over 59,000 suicides can be attributed to warming trends across the country since 1980. This effect appears to materialize through an agricultural channel in which crops are damaged, households face economic distress, and some cope by taking their own lives.

Suicide is a heartbreaking indicator of human hardship. In India, the national suicide rate has approximately doubled since 1980, from around 6 per 100,000 to over 11 per 100,000 (for reference, the rate in the U.S. is about 13 per 100,000). Due to the sheer size of India’s population, the total number of lost lives is significant; today, about 135,000 Indians commit suicide annually. There have been many claims about what contributes to the upward trend, although most focus on increasing risks in agriculture, such as output price volatility, costly hybrid seeds, and crop-damaging climate events like drought and heat (e.g. here, here, and here). While many academic and non-academic sources have discussed the role of the climate, until now there has been no quantitative evidence of a causal effect.

Over 59,000 suicides can be attributed to warming trends across India since 1980

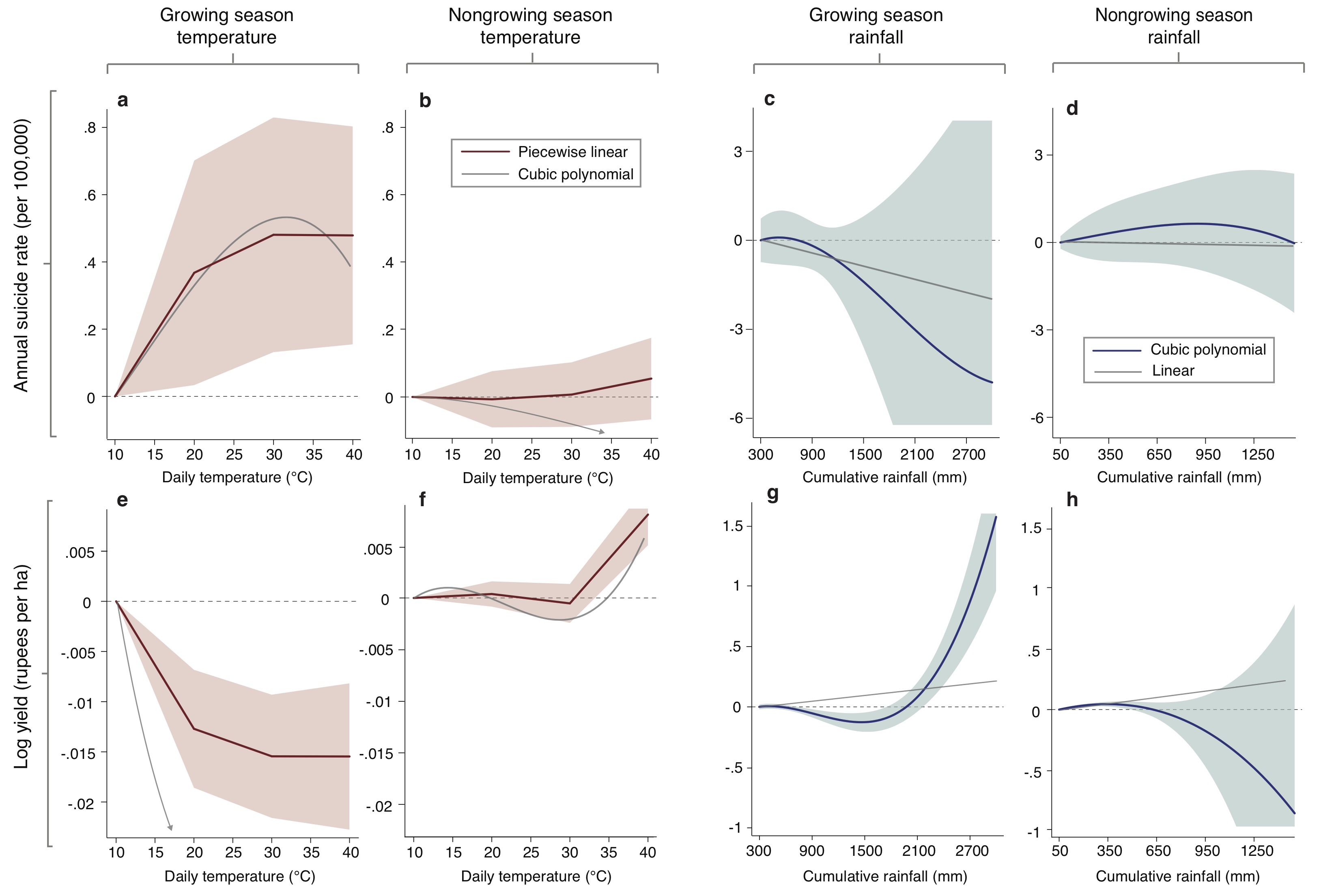

After an extensive search through all available data, Carleton finds that while growing season temperatures increase the annual suicide rate, also hurting crops, these same temperatures have no effect on suicides outside the growing season. A similar pattern emerges with rainfall: more rain during the growing season appears to cause reductions in suicide and gains in crop yields, while non-growing season rainfall has no effect.

These impacts are relatively large. Warming a single average growing season day by just 1°C throughout the country causes about 65 suicides throughout the year, equivalent to a 3.5% increase in the suicide rate per standard deviation increase in growing season temperature exposure.

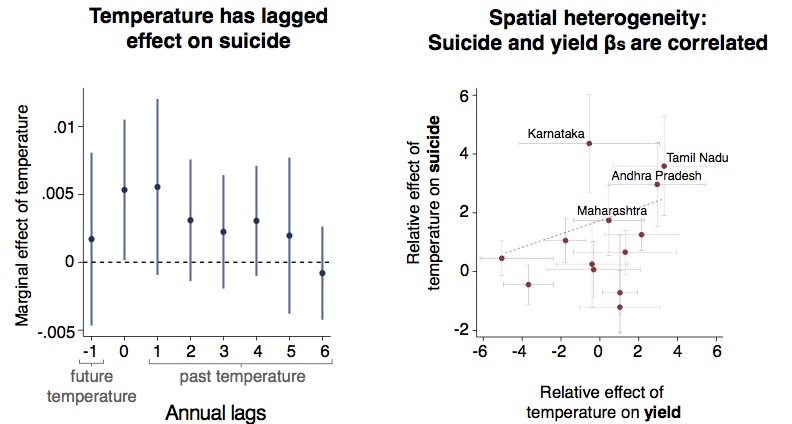

The fact that the crop response functions are mirrored by suicide response functions is consistent with a causal chain in which crop damages are the culprit linking climate to suicides. However, this evidence is only suggestive. Upon further exploration, Carleton identified substantial lagged effects of temperature and rainfall, which are unlikely to occur if non-economic, direct links between the climate and suicidal behavior were taking place (like the psychological channels linking temperature to violence discussed in the extensive literature on climate and conflict). These lagged effects indicate that benefits of rain or damages of heat to crop yields during the growing season can affect farmers in future years, perhaps through changing household savings behavior.

The study also estimates differences across locations and finds that places within India where suicides are most sensitive to growing season temperatures also tend to be where yields are most sensitive.

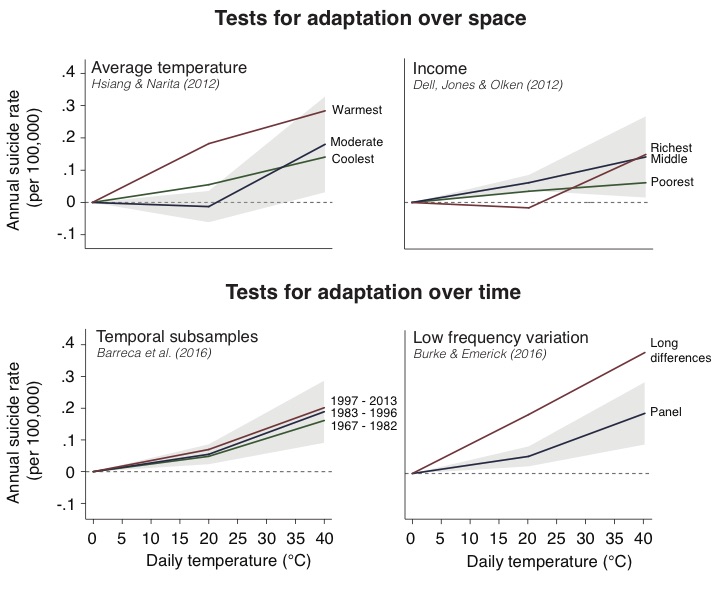

The fact that higher temperatures mean more suicides is troubling as we think about warming unfolding over the next few decades. While it is possible that populations will reallocate resources and re-optimize behaviors to adapt to a gradually warming climate, there is no clear evidence of adaptation in the historical data. This is true looking both across space (e.g. are places with hotter average climates less sensitive?) and across time (e.g. has the response function flattened over time? What about effects of more gradual temperature increases?), suggesting that without new and substantial investments in adaptation, we are likely to see more self-harm in India as temperatures rise.

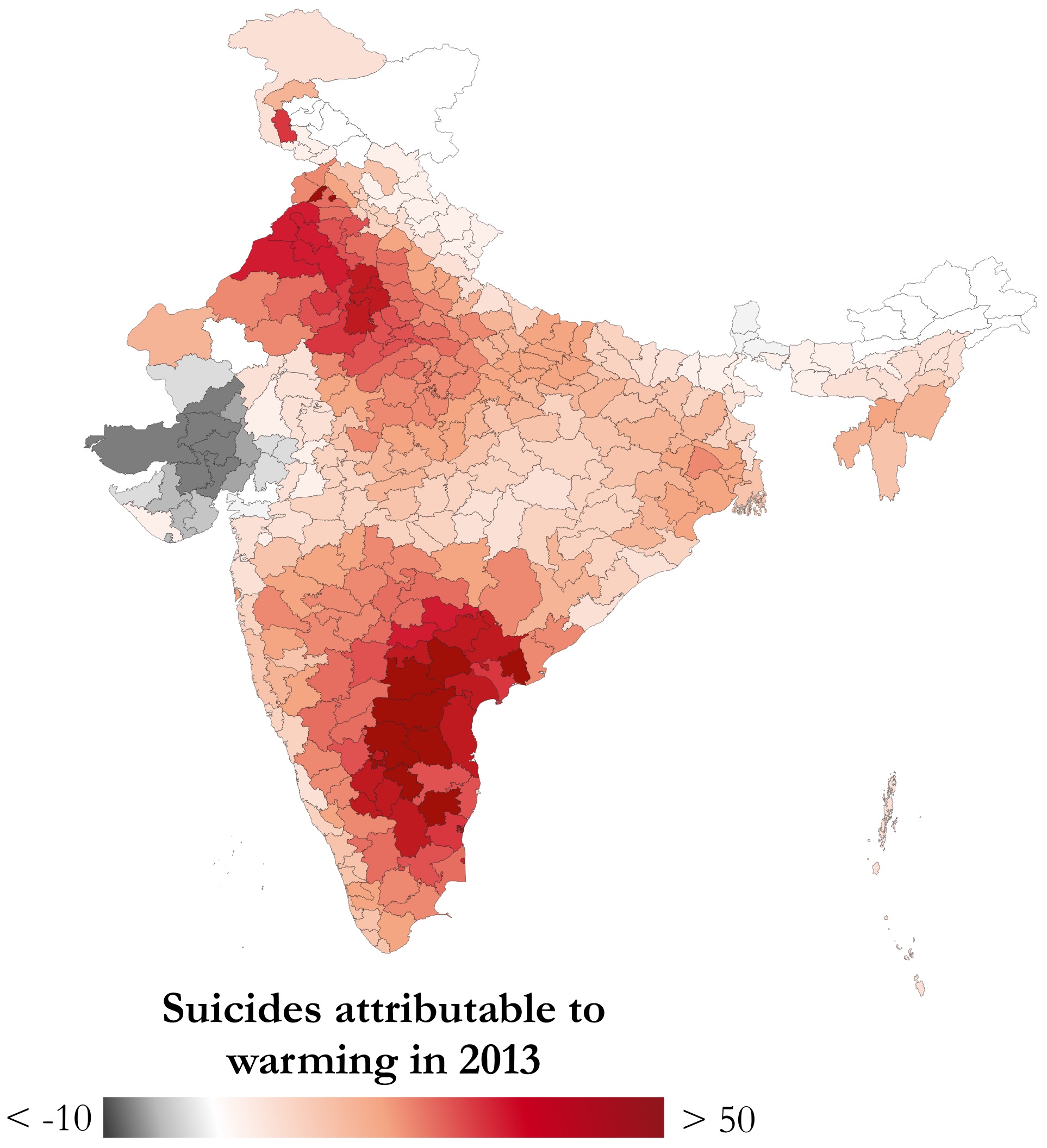

To understand the consequences of an already-changing climate, Carleton estimates the total number of deaths that can be attributed to warming trends observed throughout India since 1980. Following the method in a 2011 article in Science, as well as a recent Science paper by Carleton and Sol Hsiang, Carleton estimates that over 4,000 suicides per year across the country can be attributed to warming, totaling more than 59,000 deaths since 1980. With different warming trajectories and uneven population density across different parts of India, these deaths are distributed very unequally across space.

Developing sound social and economic policy to improve human well-being depends on our ability to understand and measure all factors that affect it

So what are the implications of this work? First, developing sound social and economic policy to improve human well-being depends on our ability to understand and measure all factors that affect it. While some aspects of how climate affects society are relatively easy to observe and measure, such as crop yields or national GDP, other key indicators of human well being are much harder to quantify. Suicide is a heartbreaking indicator of human hardship, and the finding that a changing climate has already begun to influence this phenomenon makes it an important component of our efforts to build effective policy for the future.

Second, the suicide epidemic in India has received an exceptional amount of attention in the media, yet little quantitative research exists to explain the rise in suicides. The finding that climate change plays a role in a rising suicide rate helps explain some of the upward trend in suicides observed over the last 30 years. The fact that this effect appears to materialize through crop damages provides evidence consistent with policies, like those that support well-functioning rural credit markets and crop insurance programs, seeking to reduce suicides by weakening the link between a risky climate and agricultural incomes.

Published August 15, 2017

Read